This article is from my friend Ben who runs Calibre, a tool for monitoring the performance of websites. We use Calibre here on CSS-Tricks to keep an eye on things. In fact, I just popped over there to take a look and was notified of some little mistakes that slipped by, and I fixed them. Recommended!

In this article, we uncover how PageSpeed calculates it’s critical speed score.

It’s no secret that speed has become a crucial factor in increasing revenue and lowering abandonment rates. Now that Google uses page speed as a ranking factor, many organizations have become laser-focused on performance.

Last year, Google made two significant changes to their search indexing and ranking algorithms:

- In March, indexing became based on the mobile version of a page, rather than desktop.

- In July, the SEO ranking algorithm was updated to include page speed as a ranking factor for both mobile pages and ads.

From this, we’re able to state two truths:

- The speed of your site on mobile will affect your overall SEO ranking.

- If your pages load slowly, it will reduce your ad quality score, and ads will cost more.

Google wrote:

Faster sites don’t just improve user experience; recent data shows that improving site speed also reduces operating costs. Like us, our users place a lot of value in speed — that’s why we’ve decided to take site speed into account in our search rankings.

To understand how these changes affect us from a performance perspective, we need to grasp the underlying technology. PageSpeed 5.0 is a complete overhaul of previous editions. It’s now being powered by Lighthouse and CrUX (Chrome User Experience Report).

This upgrade also brings a new scoring algorithm that makes it far more challenging to receive a high PageSpeed score.

What changed in PageSpeed 5.0?

Before 5.0, PageSpeed ran a series of heuristics against a given page. If the page has large, uncompressed images, PageSpeed would suggest image compression. Cache-Headers missing? Add them.

These heuristics were coupled with a set of guidelines that would likely result in better performance, if followed, but were merely superficial and didn’t actually analyze the load and render experience that real visitors face.

In PageSpeed 5.0, pages are loaded in a real Chrome browser that is controlled by Lighthouse. Lighthouse records metrics from the browser, applies a scoring model to them, and presents an overall performance score. Guidelines for improvement are suggested based on how specific metrics score.

Like PageSpeed, Lighthouse also has a performance score. In PageSpeed 5.0, the performance score is taken from Lighthouse directly. PageSpeed’s speed score is now the same as Lighthouse’s Performance score.

Now that we know where the PageSpeed score comes from, let’s dive into how it’s calculated, and how we can make meaningful improvements.

What is Google Lighthouse?

Lighthouse is an open source project run by a dedicated team from Google Chrome. Over the past couple of years, it has become the go-to free performance analysis tool.

Lighthouse uses Chrome’s Remote Debugging Protocol to read network request information, measure JavaScript performance, observe accessibility standards and measure user-focused timing metrics like First Contentful Paint, Time to Interactive or Speed Index.

If you’re interested in a high-level overview of Lighthouse architecture, read this guide from the official repository.

How Lighthouse calculates the Performance Score

During performance tests, Lighthouse records many metrics focused on what a user sees and experiences. There are six metrics used to create the overall performance score. They are:

- Time to Interactive (TTI)

- Speed Index

- First Contentful Paint (FCP)

- First CPU Idle

- First Meaningful Paint (FMP)

- Estimated Input Latency

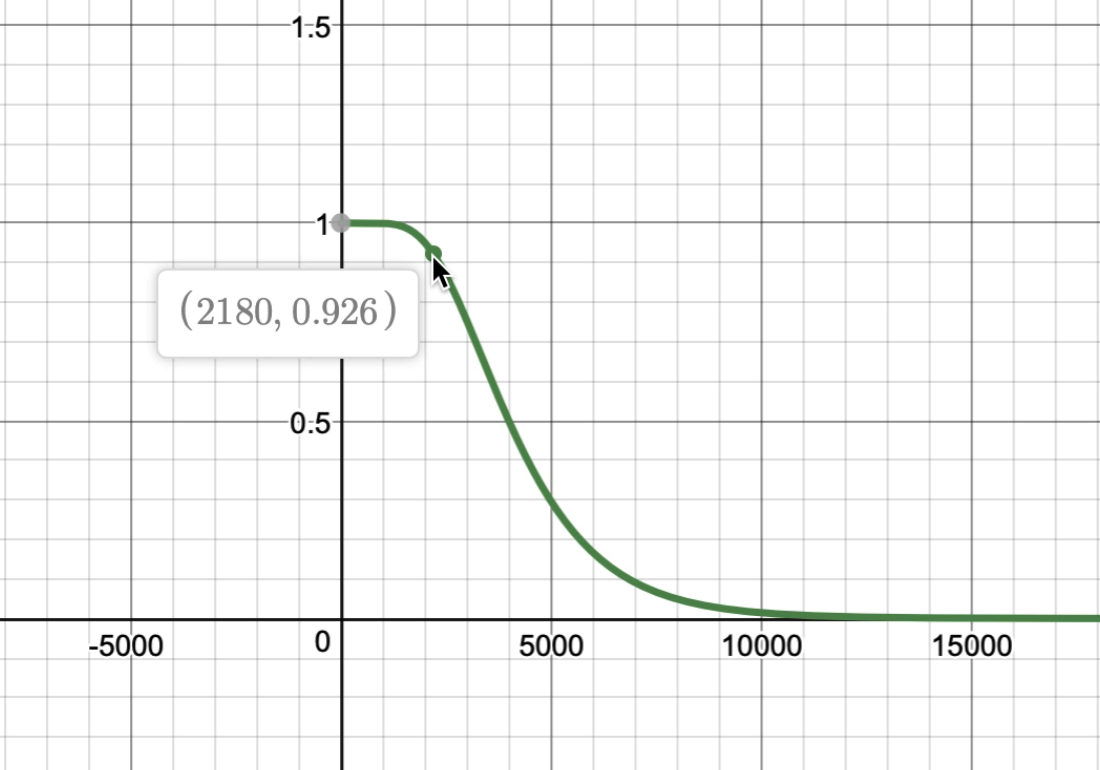

Lighthouse will apply a 0 – 100 scoring model to each of these metrics. This process works by obtaining mobile 75th and 95th percentiles from HTTP Archive, then applying a log normal function.

Following the algorithm and reference data used to calculate Time to Interactive, we can see that if a page managed to become “interactive” in 2.1 seconds, the Time to Interactive metric score would be 92/100.

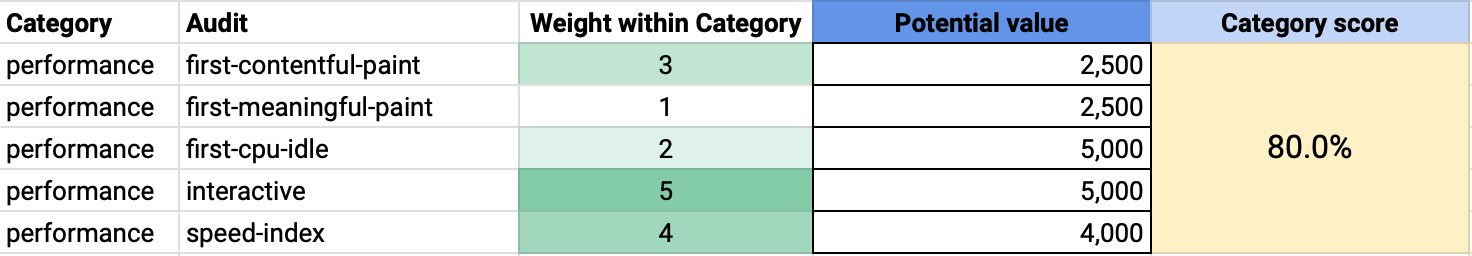

Once each metric is scored, it’s assigned a weighting which is used as a modifier in calculating the overall performance score. The weightings are as follows:

| Metric | Weighting |

|---|---|

| Time to Interactive (TTI) | 5 |

| Speed Index | 4 |

| First Contentful Paint | 3 |

| First CPU Idle | 2 |

| First Meaningful Paint | 1 |

| Estimated Input Latency | 0 |

These weightings refer to the impact of each metric in regards to mobile user experience.

In the future, this may also be enhanced by the inclusion of user-observed data from the Chrome User Experience Report dataset.

You may be wondering how the weighting of each metric affects the overall performance score. The Lighthouse team have created a useful Google Spreadsheet calculator explaining this process:

Using the example above, if we change (time to) interactive from 5 seconds to 17 seconds (the global average mobile TTI), our score drops to 56% (aka 56 out of 100).

Whereas, if we change First Contentful Paint to 17 seconds, we’d score 62%.

TTI is the most impactful metric to your performance score. Therefore, to receive a high PageSpeed score, you will need a speedy TTI measurement.

Moving the needle on TTI

At a high level, there are two significant factors that hugely influence TTI:

- The amount of JavaScript delivered to the page

- The run time of JavaScript tasks on the main thread

Our Time to Interactive guide explains how TTI works in great detail, but if you’re looking for some quick no-research wins, we’d suggest: Reducing the amount of JavaScript

Where possible, remove unused JavaScript code or focus on only delivering a script that will be run by the current page. That might mean removing old polyfills or replacing third-party libraries with smaller, more modern alternatives.

It’s important to remember that the cost of JavaScript is not only the time it takes to download it. The browser needs to decompress, parse, compile and eventually execute it, which takes non-trivial time, especially in mobile devices.

Effective measures for reducing the amount of scripts from your pages include:

- Reviewing and removing polyfills that are no longer required for your audience.

- Understanding the cost of each third-party JavaScript library. Use webpack-bundle-analyser or source-map-explorer to visualise the how large each library is.

- Modern JavaScript tooling (like webpack) can break-up large JavaScript applications into a series of small bundles that are automatically loaded as a user navigates. This approach is known as code splitting and is extremely effective in improving TTI.

- Service workers that will cache the bytecode result of a parsed and compiled script. If you’re able to make use of this, visitors will pay a one-time performance cost for parse and compilation. After that, it’ll be mitigated by cache.

Monitoring Time to Interactive

To successfully uncover significant differences in user experience, we suggest using a performance monitoring system (like Calibre!) that allows for testing a minimum of two devices; a fast desktop and a low-mid range mobile phone.

That way, you’ll have the data for both the best and worst case of what your customers experience. It’s time to come to terms that your customers aren’t using the same powerful hardware as you.

In-depth manual profiling

To get the best results in profiling JavaScript performance, test pages using intentionally slow mobile devices. If you have an old phone in a desk drawer, this is a great second-life for it.

An excellent substitute for using a real device is to use Chrome DevTools hardware emulation mode. We’ve written an extensive performance profiling guide to help you get started with runtime performance.

What about the other metrics?

Speed Index, First Contentful Paint and First Meaningful Paint are all browser-paint-based metrics. They’re influenced by similar factors and can often be improved at the same time.

It’s objectively easier to improve these metrics as they are calculated by how quickly a page renders. Following the Lighthouse Performance audit rules closely will result in these metrics improving.

If you aren’t already preloading your fonts or optimizing for critical requests, that is an excellent place to start a performance journey. Our article titled “The Critical Request” explains in great detail how the browser fetches and renders critical resources used to render your pages.

Tracking your progress and making meaningful improvements

Google’s newly updated search console, Lighthouse and PageSpeed Insights, are a great way to get initial visibility into the performance of your pages but fall short for teams that need to continuously track and improve the performance of their pages.

Continuous performance monitoring is essential to ensuring speed improvements last, and teams get instantly notified when regressions happen. Manual testing introduces unexpected variability in results and makes testing from different regions as well as on various devices nearly impossible without a dedicated lab environment.

Speed has become a crucial factor for SEO rankings, especially now that nearly 50% of web traffic comes from mobile devices.

To avoid losing your search positioning, ensure you’re using an up-to-date performance suite to track key pages. (Pssst, we built Calibre to be your performance companion. It has Lighthouse built-in. Hundreds of teams from around the globe are using it every day.)

Related Articles

- About Time to Interactive

- How to optimize the performance of a JavaScript application

- Lighthouse performance score calculator

The post How Google PageSpeed Works: Improve Your Score and Search Engine Ranking appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

0 Comments