This is your complete guide to CSS cascade layers, a CSS feature that allows us to define explicit contained layers of specificity, so that we have full control over which styles take priority in a project without relying on specificity hacks or !important. This guide is intended to help you fully understand what cascade layers are for, how and why you might choose to use them, the current levels of support, and the syntax of how you use them.

Table of Contents

- Quick example

- Introduction: what are cascade layers?

- Where do layers fit in the cascade?

- !important origins, context, and layers are reversed!

- Establishing a layer order

- Syntax: Working with cascade layers

- Use cases: When would I want to use cascade layers?

- Test your knowledge: Which style wins?

- Debugging layer conflicts in browser developer tools

- Browser support and fallbacks

- More resources

Quick example

/* establish a layer order up-front, from lowest to highest priority */

@layer reset, defaults, patterns, components, utilities, overrides;

/* import stylesheets into a layer (dot syntax represents nesting) */

@import url('framework.css') layer(components.framework);

/* add styles to layers */

@layer utilities {

/* high layer priority, despite low specificity */

[data-color='brand'] {

color: var(--brand, rebeccapurple);

}

}

@layer defaults {

/* higher specificity, but lower layer priority */

a:any-link { color: maroon; }

}

/* un-layered styles have the highest priority */

a {

color: mediumvioletred;

}Introduction: what are cascade layers?

CSS Cascade Layers are intended to solve tricky problems in CSS. Let’s take a look at the main problem and how cascade layers aim to solve it.

Problem: Specificity conflicts escalate

Many of us have been in situations where we want to override styles from elsewhere in our code (or a third-party tool), due to conflicting selectors. And over the years, authors have developed a number of “methodologies” and “best practices” to avoid these situations — such as “only using a single class” for all selectors. These rules are usually more about avoiding the cascade, rather than putting it to use.

Managing cascade conflicts and selector specificity has often been considered one of the harder — or at least more confusing — aspects of CSS. That may be partly because few other languages rely on a cascade as their central feature, but it’s also true that the original cascade relies heavily on heuristics (an educated-guess or assumption built into the code) rather than providing direct and explicit control to web authors.

Selector specificity, for example — our primary interaction with the cascade — is based on the assumption that more narrowly targeted styles (like IDs that are only used once) are likely more important than more generic and reusable styles (like classes and attributes). That is to say: how specific the selector is. That’s a good guess, but it’s not a totally reliable rule, and that causes some issues:

- It combines the act of selecting elements, with the act of prioritizing rule-sets.

- The simplest way to ‘fix’ a conflict with specificity is to escalate the problem by adding otherwise unnecessary selectors, or (gasp) throwing the

!importanthand-grenade.

.overly#powerful .framework.widget {

color: maroon;

}

.my-single_class { /* add some IDs to this ??? */

color: rebeccapurple; /* add !important ??? */

}Solution: cascade layers provide control

Cascade layers give CSS authors more direct control over the cascade so we can build more intentionally cascading systems without relying as much on heuristic assumptions that are tied to selection.

Using the @layer at-rule and layered @imports, we can establish our own layers of the cascade — building from low-priority styles like resets and defaults, through themes, frameworks, and design systems, up to highest-priority styles, like components, utilities, and overrides. Specificity is still applied to conflicts within each layer, but conflicts between layers are always resolved by using the higher-priority layer styles.

@layer framework {

.overly#powerful .framework.widget {

color: maroon;

}

}

@layer site {

.my-single_class {

color: rebeccapurple;

}

}These layers are ordered and grouped so that they don’t escalate in the same way that specificity and importance can. Cascade layers aren’t cumulative like selectors. Adding more layers doesn’t make something more important. They’re also not binary like importance — suddenly jumping to the top of a stack — or numbered like z-index, where we have to guess a big number (z-index: 9999999?). In fact, by default, layered styles are less important than un-layered styles.

@layer defaults {

a:any-link { color: maroon; }

}

/* un-layered styles have the highest priority */

a {

color: mediumvioletred;

}Where do layers fit in the cascade?

The cascade is a series of steps (an algorithm) for resolving conflicts between styles.

html { --button: teal; }

button { background: rebeccapurple !important; }

.warning { background: maroon; }<button class="warning" style="background: var(--button);">

what color background?

</button>With the addition of cascade layers, those steps are:

Selector specificity is only one small part of the cascade, but it’s also the step we interact with most, and is often used to refer more generally to overall cascade priority. People might say that the !important flag or the style attribute “adds specificity” — a quick way of expressing that the style becomes higher priority in the cascade. Since cascade layers have been added directly above specificity, it’s reasonable to think about them in a similar way: one step more powerful than ID selectors.

However, CSS Cascade Layers also make it more essential that we fully understand the role of !important in the cascade — not just as a tool for “increasing specificity” but as a system for balancing concerns.

!important origins, context, and layers are reversed!

As web authors, we often think of !important as a way of increasing specificity, to override inline styles or highly specific selectors. That works OK in most cases (if you’re OK with the escalation) but it leaves out the primary purpose of importance as a feature in the overall cascade.

Importance isn’t there to simply increase power — but to balance the power between various competing concerns.

Important origins

It all starts with origins, where a style comes from in the web ecosystem. There are three basic origins in CSS:

- The browser (or user agent)

- The user (often via browser preferences)

- Web authors (that’s us!)

Browsers provide readable defaults for all the elements, and then users set their preferences, and then we (authors) provide the intended design for our web pages. So, by default, browsers have the lowest priority, user preferences override the browser defaults, and we’re able to override everyone.

But the creators of CSS were very clear that we should not actually have the final word:

If conflicts arise the user should have the last word, but one should also allow the author to attach style hints.

— Håkon Lie (emphasis added)

So importance provides a way for the browser and users to re-claim their priority when it matters most. When the !important flag is added to a style, three new layers are created — and the order is reversed!

!importantbrowser styles (most powerful)!importantuser preferences!importantauthor styles- normal author styles

- normal user preferences

- normal browser styles (least powerful)

For us, adding !important doesn’t change much — our important styles are pretty close to our normal styles — but for the browser and user it’s a very powerful tool for regaining control. Browser default style sheets include a number of important styles that it would be impossible for us to override, such as:

iframe:fullscreen {

/* iframes in full-screen mode don't show a border. */

border: none !important;

padding: unset !important;

}While most of the popular browsers have made it difficult to upload actual user stylesheets, they all offer user preferences: a graphic interface for establishing specific user styles. In that interface, there is always a checkbox available for users to choose if a site is allowed to override their preferences or not. This is the same as setting !important in a user stylesheet:

Important context

The same basic logic is applied to context in the cascade. By default, styles from the host document (light DOM) override styles from an embedded context (shadow DOM). However, adding !important reverses the order:

!importantshadow context (most powerful)!importanthost context- normal host context

- normal shadow context (least powerful)

Important styles that come from inside a shadow context override important styles defined by the host document. Here’s an odd-bird custom element with some styles written in the element template (shadow DOM), and some styles in the host page (light DOM) stylesheet:

Both color declarations have normal importance, and so the host page mediumvioletred takes priority. But the font-family declarations are flagged !important, giving advantage to the shadow-context, where fantasy is defined.

Important layers

Cascade layers work the same way as both origins and context, with the important layers in reverse-order. The only difference is that layers make that behavior much more noticeable.

Once we start using cascade layers, we will need to be much more cautious and intentional about how we use !important. It’s no longer a quick way to jump to the top of the priorities — but an integrated part of our cascade layering; a way for lower layers to insist that some of their styles are essential.

Since cascade layers are customizable, there’s no pre-defined order. But we can imagine starting with three layers:

- utilities (most powerful)

- components

- defaults (least powerful)

When styles in those layers are marked as important, they would generate three new, reversed important layers:

!importantdefaults (most powerful)!importantcomponents!importantutilities- normal utilities

- normal components

- normal defaults (least powerful)

In this example, the color is defined by all three normal layers, and the utilities layer wins the conflict, applying the maroon color, as the utilities layer has a higher priority in @layers. But notice that the text-decoration property is marked !important in both the defaults and components layers, where important defaults take priority, applying the underline declared by defaults:

Establishing a layer order

We can create any number of layers and name them or group them in various ways. But the most important thing to do is to make sure our layers are applied in the right order of priority.

A single layer can be used multiple times throughout the codebase — cascade layers stack in the order they first appear. The first layer encountered sits at the bottom (least powerful), and the last layer at the top (most powerful). But then, above that, un-layered styles have the highest priority:

@layer layer-1 { a { color: red; } }

@layer layer-2 { a { color: orange; } }

@layer layer-3 { a { color: yellow; } }

/* un-layered */ a { color: green; }- un-layered styles (most powerful)

- layer-3

- layer-2

- layer-1 (least powerful)

Then, as discussed above, any important styles are applied in a reverse order:

@layer layer-1 { a { color: red !important; } }

@layer layer-2 { a { color: orange !important; } }

@layer layer-3 { a { color: yellow !important; } }

/* un-layered */ a { color: green !important; }!importantlayer-1 (most powerful)!importantlayer-2!importantlayer-3!importantun-layered styles- normal un-layered styles

- normal layer-3

- normal layer-2

- normal layer-1 (least powerful)

Layers can also be grouped, allowing us to do more complicated sorting of top-level and nested layers:

@layer layer-1 { a { color: red; } }

@layer layer-2 { a { color: orange; } }

@layer layer-3 {

@layer sub-layer-1 { a { color: yellow; } }

@layer sub-layer-2 { a { color: green; } }

/* un-nested */ a { color: blue; }

}

/* un-layered */ a { color: indigo; }- un-layered styles (most powerful)

- layer-3

- layer-3 un-nested

- layer-3 sub-layer-2

- layer-3 sub-layer-1

- layer-2

- layer-1 (least powerful)

Grouped layers always stay together in the final layer order (for example, sub-layers of layer-3 will all be next to each other), but this otherwise behaves the same as if the list was “flattened” — turning this into a single six-item list. When reversing !important layer order, the entire list flattened is reversed.

But layers don’t have to be defined once in a single location. We give them names so that layers can be defined in one place (to establish layer order), and then we can append styles to them from anywhere:

/* describe the layer in one place */

@layer my-layer;

/* append styles to it from anywhere */

@layer my-layer { a { color: red; } }We can even define a whole ordered list of layers in a single declaration:

@layer one, two, three, four, five, etc;This makes it possible for the author of a site to have final say over the layer order. By providing a layer order up-front, before any third party code is imported, the order can be established and rearranged in one place without worrying about how layers are used in any third-party tool.

Syntax: Working with cascade layers

Let’s take a look at the syntax!

Order-setting @layer statements

Since layers are stacked in the order they are defined, it’s important that we have a tool for establishing that order all in one place!

We can use @layer statements to do that. The syntax is:

@layer <layer-name>#;That hash (#) means we can add as many layer names as we want in a comma-separated list:

@layer reset, defaults, framework, components, utilities;That will establish the layer order:

- un-layered styles (most powerful)

- utilities

- components

- framework

- defaults

- reset (least powerful)

We can do this as many times as we want, but remember: what matters is the order each name first appears. So this will have the same result:

@layer reset, defaults, framework;

@layer components, defaults, framework, reset, utilities;The ordering logic will ignore the order of reset, defaults, and framework in the second @layer rule because those layers have already been established. This @layer list syntax doesn’t add any special magic to the layer ordering logic: layers are stacked based on the order in which the layers first appear in your code. In this case, reset appears first in the first @layer list. Any @layer statement that comes later can only append layer names to the list, but can’t move layers that already exist. This ensures that you can always control the final overall layer order from one location — at the very start of your styles.

These layer-ordering statements are allowed at the top of a stylesheet, before the @import rule (but not between imports). We highly recommend using this feature to establish all your layers up-front in a single place so you always know where to look or make changes.

Block @layer rules

The block version of the @layer rule only takes a single layer name, but then allows you to add styles to that layer:

@layer <layer-name> {

/* styles added to the layer */

}You can put most things inside an @layer block — media queries, selectors and styles, support queries, etc. The only things you can’t put inside a layer block are things like charset, imports, and namespaces. But don’t worry, there is a syntax for importing styles into a layer.

If the layer name hasn’t been established before, this layer rule will add it to the layer order. But if the name has been established, this allows you to add styles to existing layers from anywhere in the document — without changing the priority of each layer.

If we’ve established our layer-order up-front with the layer statement rule, we no longer need to worry about the order of these layer blocks:

/* establish the order up-front */

@layer defaults, components, utilities;

/* add styles to layers in any order */

@layer utilities {

[hidden] { display: none; }

}

/* utilities will override defaults, based on established order */

@layer defaults {

* { box-sizing: border-box; }

img { display: block; }

}Grouping (nested) layers

Layers can be grouped, by nesting layer rules:

@layer one {

/* sorting the sub-layers */

@layer two, three;

/* styles ... */

@layer three { /* styles ... */ }

@layer two { /* styles ... */ }

}This generates grouped layers that can be represented by joining the parent and child names with a period. That means the resulting sub-layers can also be accessed directly from outside the group:

/* sorting nested layers directly */

@layer one.two, one.three;

/* adding to nested layers directly */

@layer one.three { /* ... */ }

@layer one.two { /* ... */ }The rules of layer-ordering apply at each level of nesting. Any styles that are not further nested are considered “un-layered” in that context, and have priority over further nested styles:

@layer defaults {

/* un-layered defaults (higher priority) */

:any-link { color: rebeccapurple; }

/* layered defaults (lower priority) */

@layer reset {

a[href] { color: blue; }

}

}Grouped layers are also contained within their parent, so that the layer order does not intermix across groups. In this example, the top level layers are sorted first, and then the layers are sorted within each group:

@layer reset.type, default.type, reset.media, default.media;Resulting in a layer order of:

- un-layered (most powerful)

- default group

- default un-layered

- default.media

- default.type

- reset group

- reset un-layered

- reset.media

- reset.type

Note that layer names are also scoped so that they don’t interact or conflict with similarly-named layers outside their nested context. Both groups can have distinct media sub-layers.

This grouping becomes especially important when using @import or <link> to layer entire stylesheets. A third-party tool, like Bootstrap, could use layers internally — but we can nest those layers into a shared bootstrap layer-group on import, to avoid potential layer-naming conflicts.

Layering entire stylesheets with @import or <link>

Entire stylesheets can be added to a layer using the new layer() function syntax with @import rules:

/* styles imported into to the <layer-name> layer */

@import url('example.css') layer(<layer-name>);There is also a proposal to add a layer attribute in the HTML <link> element — although this is still under development, and not yet supported anywhere. This can be used to import third-party tools or component libraries, while grouping any internal layers together under a single layer name — or as a way of organizing layers into distinct files.

Anonymous (un-named) layers

Layer names are helpful as they allow us to access the same layer from multiple places for sorting or combining layer blocks — but they are not required.

It’s possible to create anonymous (un-named) layers using the block layer rule:

@layer { /* ... */ }

@layer { /* ... */ }Or using the import syntax, with a layer keyword in place of the layer() function:

/* styles imported into to a new anonymous layer */

@import url('../example.css') layer;Each anonymous layer is unique, and added to the layer order where it is encountered. Anonymous layers can’t be referenced from other layer rules for sorting or appending more styles.

These should probably be used sparingly, but there might be a few use cases:

- Projects could ensure that all styles for a given layer are required to be located in a single place.

- Third-party tools could “hide” their internal layering inside anonymous layers so that they don’t become part of the tool’s public API.

Reverting values to the previous layer

There are several ways that we can use to “revert” a style in the cascade to a previous value, defined by a lower priority origin or layer. That includes a number of existing global CSS values, and a new revert-layer keyword that will also be global (works on any property).

Context: Existing global cascade keywords*

CSS has several global keywords which can be used on any property to help roll-back the cascade in various ways.

initialsets a property to the specified value before any styles (including browser defaults) are applied. This can be surprising as we often think of browser styles as the initial value — but, for example, theinitialvalue ofdisplayisinline, no matter what element we use it on.inheritsets the property to apply a value from its parent element. This is the default for inherited properties, but can still be used to remove a previous value.unsetacts as though simply removing all previous values — so that inherited properties once againinherit, while non-inherited properties return to theirinitialvalue.revertonly removes values that we’ve applied in the author origin (i.e. the site styles). This is what we want in most cases, since it allows the browser and user styles to remain intact.

New: the revert-layer keyword

Cascade layers add a new global revert-layer keyword. It works the same as revert, but only removes values that we’ve applied in the current cascade layer. We can use that to roll back the cascade, and use whatever value was defined in the previous layers.

In this example, the no-theme class removes any values set in the theme layer.

@layer default {

a { color: maroon; }

}

@layer theme {

a { color: var(--brand-primary, purple); }

.no-theme {

color: revert-layer;

}

}So a link tag with the .no-theme class will roll back to use the value set in the default layer. When revert-layer is used in un-layered styles, it behaves the same as revert — rolling back to the previous origin.

Reverting important layers

Things get interesting if we add !important to the revert-layer keyword. Because each layer has two distinct “normal” and “important” positions in the cascade, this doesn’t simply change the priority of the declaration — it changes what layers are reverted.

Let’s assume we have three layers defined, in a layer stack that looks like this:

- utilities (most powerful)

- components

- defaults (least powerful)

We can flesh that out to include not just normal and important positions of each layer, but also un-layered styles, and animations:

!importantdefaults (most powerful)!importantcomponents!importantutilities!importantun-layered styles- CSS animations

- normal un-layered styles

- normal utilities

- normal components

- normal defaults (least powerful)

Now, when we use revert-layer in a normal layer (let’s use utilities) the result is fairly direct. We revert only that layer, while everything else applies normally:

- ✅

!importantdefaults (most powerful) - ✅

!importantcomponents - ✅

!importantutilities - ✅

!importantun-layered styles - ✅ CSS animations

- ✅ normal un-layered styles

- ❌ normal utilities

- ✅ normal components

- ✅ normal defaults (least powerful)

But when we move that revert-layer into the important position, we revert both the normal and important versions along with everything in-between:

- ✅

!importantdefaults (most powerful) - ✅

!importantcomponents - ❌

!importantutilities - ❌

!importantun-layered styles - ❌ CSS animations

- ❌ normal un-layered styles

- ❌ normal utilities

- ✅ normal components

- ✅ normal defaults (least powerful)

Use cases: When would I want to use cascade layers?

So what sort of situations might we find ourselves using cascade layers? Here are several examples of when cascade layers make a lot of sense, as well as others where they do not make a lot sense.

Less intrusive resets and defaults

One of the clearest initial use cases would be to make low-priority defaults that are easy to override.

Some resets have been doing this already by applying the :where() pseudo-class around each selector. :where() removes all specificity from the selectors it is applied to, which has the basic impact desired, but also some downsides:

- It has to be applied to each selector individually

- Conflicts inside the reset have to be resolved without specificity

Layers allow us to more simply wrap the entire reset stylesheet, either using the block @layer rule:

/* reset.css */

@layer reset {

/* all reset styles in here */

}Or when you import the reset:

/* reset.css */

@import url(reset.css) layer(reset);Or both! Layers can be nested without changing their priority. This way, you can use a third-party reset, and ensure it gets added to the layer you want whether or not the reset stylesheet itself is written using layers internally.

Since layered styles have a lower priority than default “un-layered” styles, this is a good way to start using cascade layers without re-writing your entire CSS codebase.

The reset selectors still have specificity information to help resolve internal conflicts, without wrapping each individual selector — but you also get the desired outcome of a reset stylesheet that is easy to override.

Managing a complex CSS architecture

As projects become larger and more complex, it can be useful to define clearer boundaries for naming and organizing CSS code. But the more CSS we have, the more potential we have for conflicts — especially from different parts of a system like a “theme” or a “component library” or a set of “utility classes.”

Not only do we want these organized by function, but it can also be useful to organize them based on what parts of the system take priority in the case of a conflict. Harry Robert’s Inverted Triangle CSS does a good job visualizing what those layers might contain.

In fact, the initial pitch for adding layers to the CSS cascade used the ITCSS methodology as a primary example, and a guide for developing the feature.

There is no particular technique required for this, but it’s likely helpful to restrict projects to a pre-defined set of top-level layers and then extend that set with nested layers as appropriate.

For example:

- low level reset and normalization styles

- element defaults, for basic typography and legibility

- themes, like light and dark modes

- re-usable patterns that might appear across multiple components

- layouts and larger page structures

- individual components

- overrides and utilities

We can create that top-level layer stack at the very start of our CSS, with a single layer statement:

@layer

reset,

default,

themes,

patterns,

layouts,

components,

utilities;The exact layers needed, and how you name those layers, might change from one project to the next.

From there, we create even more detailed layer breakdowns. Maybe our components themselves have defaults, structures, themes, and utilities internally.

@layer components {

@layer defaults, structures, themes, utilities;

}Without changing the top-level structure, we now have a way to further layer the styles within each component.

Using third-party tools and frameworks

Integrating third-party CSS with a project is one of the most common places to run into cascade issues. Whether we’re using a shared reset like Normalizer or CSS Remedy, a generic design system like Material Design, a framework like Bootstrap, or a utility toolkit like Tailwind — we can’t always control the selector specificity or importance of all the CSS being used on our sites. Sometimes, this even extends to internal libraries, design systems, and tools managed elsewhere in an organization.

As a result, we often have to structure our internal CSS around the third-party code, or escalate conflicts when they come up — with artificially high specificity or !important flags. And then we have to maintain those hacks over time, adapting to upstream changes.

Cascade layers give us a way to slot third-party code into the cascade of any project exactly where we want it to live — no matter how selectors are written internally. Depending on the type of library we’re using, we might do that in various ways. Let’s start with a basic layer-stack, working our way up from resets to utilities:

@layer reset, type, theme, components, utilities;And then we can incorporate some tools…

Using a reset

If we’re using a tool like CSS Remedy, we might also have some reset styles of our own that we want to include. Let’s import CSS Remedy into a sub-layer of reset:

@import url('remedy.css') layer(reset.remedy);Now we can add our own reset styles to the reset layer, without any further nesting (unless we want it). Since styles directly in reset will override any further nested styles, we can be sure our styles will always take priority over CSS Remedy if there’s a conflict — no matter what changes in a new release:

@import url('remedy.css') layer(reset.remedy);

@layer reset {

:is(ol, ul)[role='list'] {

list-style: none;

padding-inline-start: 0;

}

}And since the reset layer is at the bottom of the stack, the rest of the CSS in our system will override both Remedy, and our own local reset additions.

Using utility classes

At the other end of our stack, “utility classes” in CSS can be a useful way to reproduce common patterns (like additional context for screen readers) in a broadly-applicable way. Utilities tend to break the specificity heuristic, since we want them defined broadly (resulting in a low specificity), but we also generally want them to “win” conflicts.

By having a utilities layer at the top of our layer stack, we can make that possible. We can use that in a similar way to the reset example, both loading external utilities into a sub-layer, and providing our own:

@import url('tailwind.css') layer(utilities.tailwind);

@layer utilities {

/* from https://kittygiraudel.com/snippets/sr-only-class/ */

/* but with !important removed from the properties */

.sr-only {

border: 0;

clip: rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px);

-webkit-clip-path: inset(50%);

clip-path: inset(50%);

height: 1px;

overflow: hidden;

margin: -1px;

padding: 0;

position: absolute;

width: 1px;

white-space: nowrap;

}

}Using design systems and component libraries

There are a lot of CSS tools that fall somewhere in the middle of our layer stack — combining typography defaults, themes, components, and other aspects of a system.

Depending on the particular tool, we might do something similar to the reset and utility examples above — but there are a few other options. A highly integrated tool might deserve a top-level layer:

@layer reset, bootstrap, utilities;

@import url('bootstrap.css') layer(bootstrap);If these tools start to provide layers as part of their public API, we could also break it down into parts — allowing us to intersperse our code with the library:

@import url('bootstrap/reset.css') layer(reset.bootstrap);

@import url('bootstrap/theme.css') layer(theme.bootstrap);

@import url('bootstrap/components.css') layer(components.bootstrap);

@layer theme.local {

/* styles here will override theme.bootstrap */

/* but not interfere with styles from components.bootstrap */

}Using layers with existing (un-layered, !important-filled) frameworks

As with any major language change, there’s going to be an adjustment period when CSS Cascade Layers become widely adopted. What happens if your team is ready to start using layers next month, but your favorite framework decides to wait another three years before they switch over to layered styles? Many frameworks will likely still use !important more often than we’d like! With !important layers reversed, that’s not ideal.

Still, layers can still help us solve the problem. We just have to get clever about it. We decide what layers we want for our project, and that means we can add layers above and also below the framework layers we create.

For now, though, we can use a lower layer to override !important styles from the framework, and a higher layer to override normal styles. Something like this:

@layer framework.important, framework.bootstrap, framework.local;

@import url('bootstrap.css') layer(framework.bootstrap);

@layer framework.local {

/* most of our normal framework overrides can live here */

}

@layer framework.important {

/* add !important styles in a lower layer */

/* to override any !important framework styles */

}It still feels like a bit of a hack, but it helps move us in the right direction — towards a more structured cascade. Hopefully it’s a temporary fix.

Designing a CSS tool or framework

For anyone maintaining a CSS library, cascade layers can help with internal organization, and even become part of the developer API. By naming internal layers of a library, we can allow users of our framework to hook into those layers when customizing or overriding our provided styles.

For example, Bootstrap could expose layers for their “reboot,” “grid,” and “utilities” — likely stacked in that order. Now a user can decide if they want to load those Bootstrap layers into different local layers:

@import url(bootstrap/reboot.css) layer(reset); /* reboot » reset.reboot */

@import url(bootstrap/grid.css) layer(layout); /* grid » layout.grid */

@import url(bootstrap/utils.css) layer(override); /* utils » override.utils */Or the user might load them into a Bootstrap layer, with local layers interspersed:

@layer bs.reboot, bs.grid, bs.grid-overrides, bs.utils, bs.util-overrides;

@import url('bootstrap-all.css') layer(bs);It’s also possible to hide internal layering from users, when desired, by grouping any private/internal layers inside an anonymous (un-named) layer. Anonymous layers will get added to the layer order where they are encountered, but will not be exposed to users re-arranging or appending styles.

I just want this one property to be more !important

Counter to some expectations, layers don’t make it easy to quickly escalate a particular style so that it overrides another.

If the majority of our styles are un-layered, then any new layer will be de-prioritized in relation to the default. We could do that to individual style blocks, but it would quickly become difficult to track.

Layers are intended to be more foundational, not style-by-style, but establishing consistent patterns across a project. Ideally, if we’ve set that up right, we get the correct result by moving our style to the appropriate (and pre-defined) layer.

If the majority of our styles already fall into well-defined layers, we can always consider adding a new highest-power layer at the top of a given stack, or using un-layered styles to override the layers. We might even consider having a debug layer at the top of the stack, for doing exploratory work outside of production.

But adding new layers on-the-fly can defeat the organizational utility of this feature, and should be used carefully. It’s best to ask: Why should this style override the other?

If the answer has to do with one type of style always overriding another type, layers are probably the right solution. That might be because we’re overriding styles that come from a place we don’t control, or because we’re writing a utility, and it should move into our utilities layer. If the answer has to do with more targeted styles overriding less targeted styles, we might consider making the selectors reflect that specificity.

Or, on rare occasions, we might even have styles that really are important — the feature simply doesn’t work if you override this particular style. We might say adding display: none to the [hidden] attribute belongs in our lowest-priority reset, but should still be hard to override. In that case, !important really is the right tool for the job:

@layer reset {

[hidden] { display: none !important; }

}Scoping and name-spacing styles? Nope!

Cascade layers are clearly an organizational tool, and one that ‘captures’ the impact of selectors, especially when they conflict. So it can be tempting at first glance to see them as a solution for managing scope or name-spacing.

A common first-instinct is to create a layer for each component in a project — hoping that will ensure (for example) that .post-title is only applied inside a .post.

But cascade conflicts are not the same as naming conflicts, and layers aren’t particularly well designed for this type of scoped organization. Cascade layers don’t constrain how selectors match or apply to the HTML, only how they cascade together. So unless we can be sure that component X always override component Y, individual component layers won’t help much. Instead, we’ll need to keep an eye on the proposed @scope spec that is being developed.

It can be useful to think of layers and component-scopes instead as overlapping concerns:

Scopes describe what we are styling, while layers describe why we are styling. We can also think of layers as representing where the style comes from, while scopes represent what the style will attach to.

Test your knowledge: Which style wins?

For each situation, assume this paragraph:

<p id="intro">Hello, World!</p>Question 1

@layer ultra-high-priority {

#intro {

color: red;

}

}

p {

color: green;

}What color is the paragraph?

Despite the layer having a name that sounds pretty important, un-layered styles have a higher priority in the cascade. So the paragraph will be green.

Question 2

@layer ren, stimpy;

@layer ren {

p { color: red !important; }

}

p { color: green; }

@layer stimpy {

p { color: blue !important; }

}What color is the paragraph?

Our normal layer order is established at the start — ren at the bottom, then stimpy, then (as always) un-layered styles at the top. But these styles aren’t all normal, some of them are important. Right away, we can filter down to just the !important styles, and ignore the unimportant green. Remember that ‘origins and importance’ are the first step of the cascade, before we even take layering into account.

That leaves us with two important styles, both in layers. Since our important layers are reversed, ren moves to the top, and stimpy to the bottom. The paragraph will be red.

Question 3

@layer Montagues, Capulets, Verona;

@layer Montagues.Romeo { #intro { color: red; } }

@layer Montagues.Benvolio { p { color: orange; } }

@layer Capulets.Juliet { p { color: yellow; } }

@layer Verona { * { color: blue; } }

@layer Capulets.Tybalt { #intro { color: green; } }What color is the paragraph?

All our styles are in the same origin and context, none are marked as important, and none of them are inline styles. We do have a broad range of selectors here, from a highly specific ID #intro to a zero specificity universal * selector. But layers are resolved before we take specificity into account, so we can ignore the selectors for now.

The primary layer order is established up front, and then sub-layers are added internally. But sub-layers are sorted along with their parent layer — meaning all the Montagues will have lowest priority, followed by all the Capulets, and then Verona has final say in the layer order. So we can immediately filter down to just the Verona styles, which take precedence. Even though the * selector has zero specificity, it will win.

Be careful about putting universal selectors in powerful layers!

Debugging layer conflicts in browser developer tools

Chrome, Safari, Firefox, and Edge browsers all have developer tools that allow you to inspect the styles being applied to a given element on the page. The styles panel of this element inspector will show applied selectors, sorted by their cascade priority (highest priority at the top), and then inherited styles below. Styles that are not being applied for any reason will generally be grayed out, or even crossed out — sometimes with additional information about why the style is not applied. This is the first place to look when debugging any aspect of the cascade, including layer conflicts.

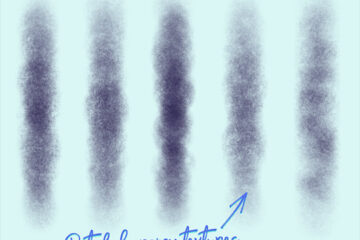

Safari Technology Preview and Firefox Nightly already show (and sort) cascade layers in this panel. This tooling is expected to role out in the stable versions at the same time as cascade layers. The layer of each selector is listed directly above the selector itself:

Chrome/Edge are working on similar tools and expect to have them available in Canary (nightly) releases by the time cascade layers land in the stable release. We’ll make updates here as those tools change and improve.

Browser support and fallbacks

Cascade layers are (or will soon be) available by default in all the three major browser engines:

- Chrome/Edge 99+

- Firefox 97+

- Safari (currently in the Technology Preview)

Since layers are intended as foundational building blocks of an entire CSS architecture, it is difficult to imagine building manual fallbacks in the same way you might for other CSS features. The fallbacks would likely involve duplicating large sections of code, with different selectors to manage cascade layering — or providing a much simpler fallback stylesheet.

Query feature support using @supports

There is a @supports feature in CSS that will allow authors to test for support of @layer and other at-rules:

@supports at-rule(@layer) {

/* code applied for browsers with layer support */

}

@supports not at-rule(@layer) {

/* fallback applied for browsers without layer support */

}However, it’s also not clear when this query itself will be supported in browsers.

Assigning layers in HTML with the <link> tag

There is no official specification yet for a syntax to layer entire stylesheets from the html <link> tag, but there is a proposal being developed. That proposal includes a new layer attribute which can be used to assign the styles to a named or anonymous layer:

<!-- styles imported into to the <layer-name> layer -->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="example.css" layer="<layer-name>">

<!-- styles imported into to a new anonymous layer -->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="example.css" layer>However, old browsers without support for the layer attribute will ignore it completely, and continue to load the stylesheet without any layering. The results could be pretty unexpected. So the proposal also extends the existing media attribute, so that it allows feature support queries in a support() function.

That would allow us to make layered links conditional, based on support for layering:

<link rel="stylesheet" layer="bootstrap" media="supports(at-rule(@layer))" href="bootstrap.css">Potential polyfills and workarounds

The major browsers have all moved to an “evergreen” model with updates pushed to users on a fairly short release cycle. Even Safari regularly releases new features in “patch” updates between their more rare-seeming major versions.

That means we can expect browser support for these features to ramp up very quickly. For many of us, it may be reasonable to start using layers in only a few months, without much concern for old browsers.

For others, it may take longer to feel comfortable with the native browser support. There are many other ways to manage the cascade, using selectors, custom properties, and other tools. It’s also theoretically possible to mimic (or polyfill) the basic behavior. There are people working on that polyfill, but it’s not clear when that will be ready either.

More resources

CSS Cascade Layers is still evolving but there is already a lot of resources, including documentation, articles, videos, and demos to help you get even more familiar with layers and how they work.

Reference

Articles

- The Future of CSS: Cascade Layers (CSS

@layer) by Bramus Van Damme - Getting Started With CSS Cascade Layers by Stephanie Eckles, Smashing Magazine

- Cascade layers are coming to your browser by Una Kravets, Chrome Developers

Videos

- How does CSS !important actually work? by Una Kravets

- An overview of the new @layer and layer() CSS primitives by Una Kravets

- CSS Revert & Revert-Layer Keywords by Una Kravets

Demos

A Complete Guide to CSS Cascade Layers originally published on CSS-Tricks. You should get the newsletter.

0 Comments